The Single-Family Space Colony, Part I

Are Space Cowboy or State Astronaut my only career choices?

In his book Frame Innovation, Kees Dorst describes a design methodology for “solving the unsolvable” problems that face us—issues that are complex, interlinked, ambiguous, with no clear criteria for resolution and often no clear definition. Designers can solve such problems by reframing them: essentially, redescribing them using new language. Sometimes, doing this provides an almost miraculous insight into what’s wrong and how to fix it.

I refer to this approach in my novel Stealing Worlds but don’t actually show how it’s done. I needed a good example, and found one that I can show off here as a “design fiction.” Part II is literally going to include blueprints, so this is going to be fun.

You might not think settling space is problematic at all. We can either do it or we can’t. But in this first part of a two-part series, I’ll show that in fact our current models of space colonization are deeply problematic, by reframing them in a new context: that of the family home.

Dorst’s model of frame analysis has nine stages. I’ll start with his first stage: Archaeology—the history of the problem. I don’t have time here to describe each stage, but I’ll name them in the headings as I go.

Archaeology: Tatooine or Island Three

Star Wars came out when I was fifteen; I went to see it with my mom at the Towne Cinema, one of two movie theaters we had in Brandon, Manitoba. I liked the movie well enough, and I understand it blew a lot of people’s minds and turned thousands if not millions onto science fiction. Mom had introduced me to her shelf of Andre Norton novels, so I was right there with it, but the movie didn’t blow my mind. Not because it wasn’t great, but because something else had come out that same year—a book, not another movie. My imagination was spinning in entirely different directions because I had just read Gerard K. O’Neill’s The High Frontier.

In Star Trek and Star Wars and in the imaginations of pretty much every science fiction writer, space had always been the empty wilderness between towns. It was the rutted track that the wagon train to the stars took; it was the blank line between scenes. —That is until The High Frontier was published. (The equally magisterial Colonies in Space, by T. A. Heppenheimer, came out the following year.)

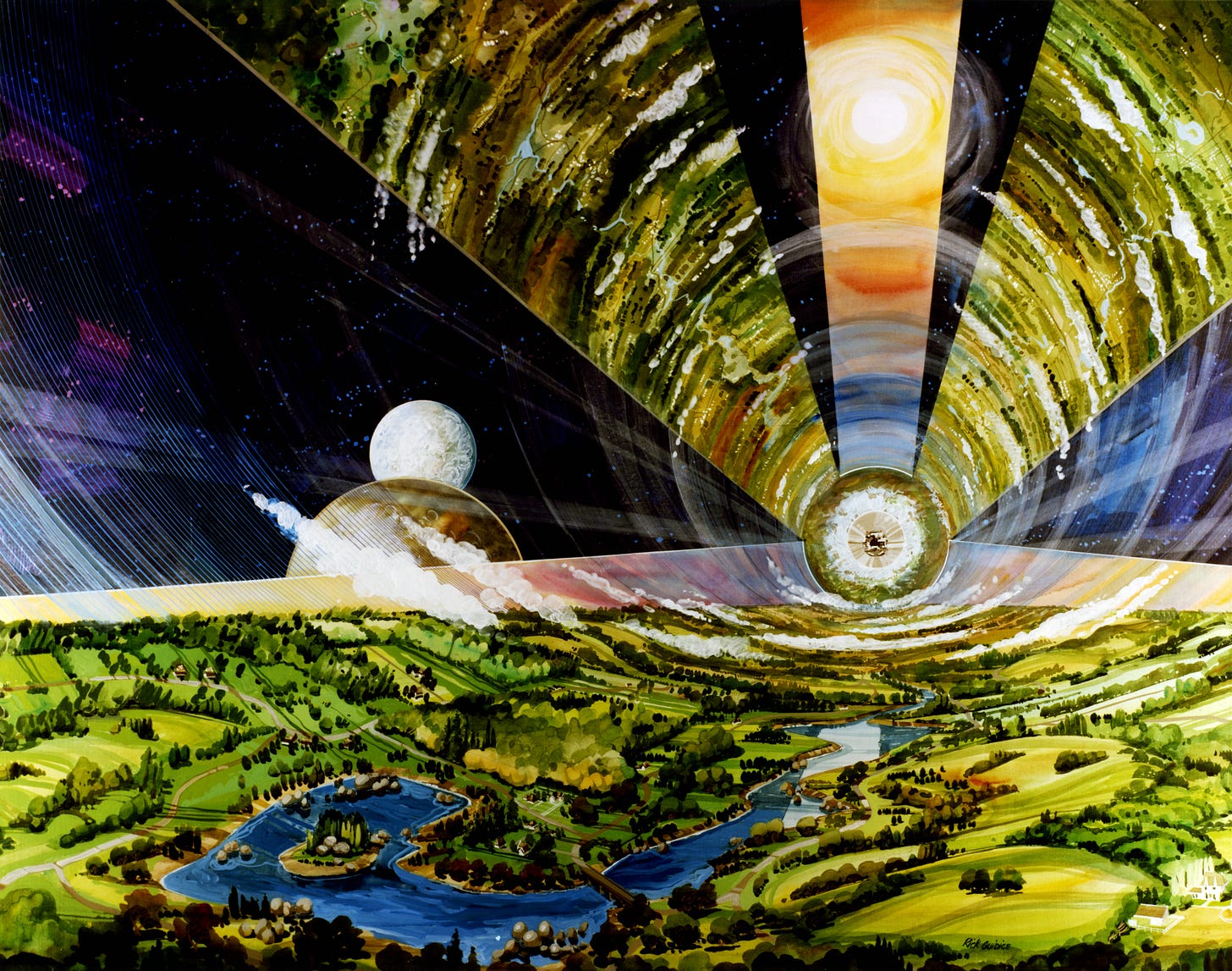

To O’Neill and Heppenheimer, space wasn’t the featureless highway between the moon, the asteroids, Mars, and the other planets. Space was the destination. The planets were just there to be mined on the way by.

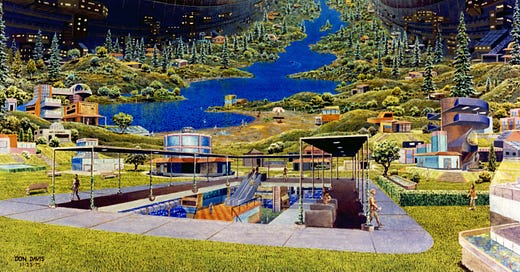

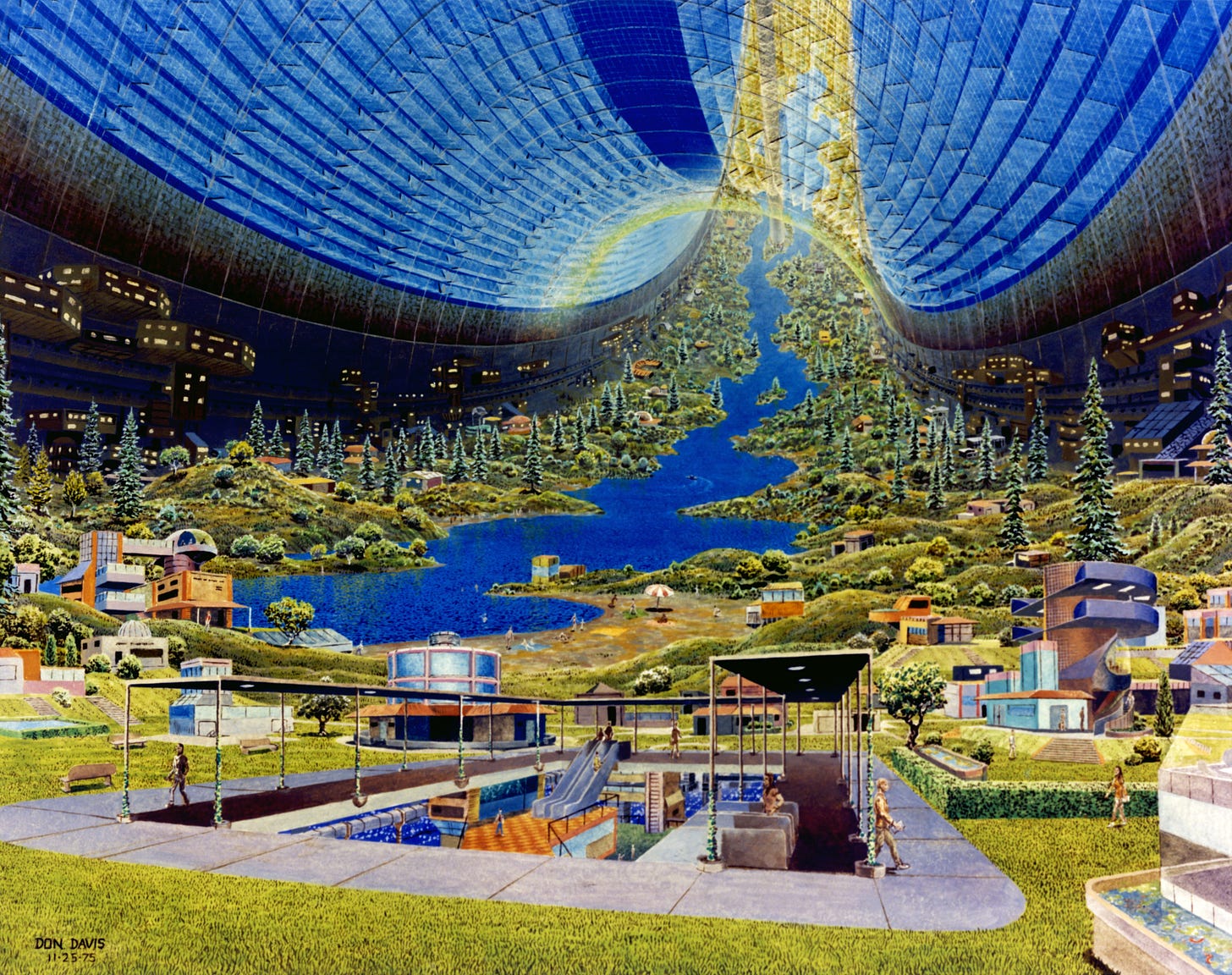

Open, empty space has a decisive advantage over any planet. There, we can build earthlike homesteads on whatever scale we want. In The High Frontier, O’Neill described successively bigger space habitats, which he called islands. These were more than just shirt-sleeve environments, they were big enough to hold cities, plains of grass, bees and birds, and miles and miles of open countryside under skies festooned with clouds. With 1970s technology, we could duplicate Earth in space, anywhere, and innumerable times. The largest structure that O’Neill describes in detail is the Island Three, which could contain 300 square kilometers of land, water, forest, and city.

After I read O’Neill and Heppenheimer, I could no longer see the other planets in our Solar system as places to settle. Unless a world has the right gravity and it’s possible for humans to go outside without a spacesuit, it can never be home. There has to be an outside that includes the beings we co-evolved with. Traditional space stations have the same problem. We didn’t evolve to live alone, entirely inside buildings, on Earth, or off it.

To my fifteen-year-old self, it was obvious what the future was going to look like. It wouldn’t be anything like Star Wars. I just had to wait, and in a little while, islands would blossom in the sky.

Paradox: two visions and a missing middle

O’Neill thought that we’d be colonizing space by the 1980s. That didn’t happen. It’s easy to blame the short-sightedness of post-Apollo spending for the long drought in spaceflight between Apollo and Artemis; while it was a magnificent technological leap forward, the Space Shuttle was also a mess of compromises--too incredibly expensive for regular use yet not powerful enough to reach high orbits with large payloads. The International Space Station is also just what it says it is and no more: it’s a tool for enhancing international cooperation rather than an attempt to kickstart a true space economy. For that, you need cheap heavy-lift launch capability, which we are only now developing but could have had since the ‘70s.

Lately, Elon Musk is advocating for the settlement of Mars driven by commercial and private entities. Jeff Bezos financed the later seasons of the TV show The Expanse, which shows a Solar System ruled by planetary politics and neoliberal economics. (The Expanse’s model of domestic life in space is the company town; if you want to know what life in a company town is like, read Kate Beaton’s fantastic graphic novel, Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands.)

Looking as a designer at the archetypal romances that dominate our future in space, it seems to me that in the public imagination, the possibilities have split into two diametrically opposed narratives with an excluded middle. It’s either Island Three or Tatooine; and neither of these alternatives provides incentives for people to leave Earth.

I’m going to argue that the missing middle contains vast possibilities, and ultimately, the path to an entirely new aspiration for off-planet life.

The anarchies of Star Wars and The Expanse exemplify an oligarchic, corporatist vision of space conquest; Star Trek and O’Neill’s gigantic islands, a collectivist alternative. (Yes, this is a vast simplification, but my point is precisely that we have simplified the options in our imaginations; boiled down, we get these two.) There’s a missing middle: when was the last time you read or watched a story about a stable middle-class life in space? There is no visible middle class in Star Wars, nor in The Expanse. Only governments or very large corporate powers could build an O’Neill cylinder; the people who live in them are tenants, not owners.

O’Neill assumed we would start by conjuring what amounts to entire countries out of nothing. Even if SpaceX and the Gateway Foundation can bring launch and construction costs down by orders of magnitude, it still seems that only governments or giant consortia—the Apples, Exxons, and Hyundais of the world—are going to control where you work, live, and play in the high frontier.

Right now, our future in space is the company town or its government equivalent.

Context and Field: What’s my stake in all of this?

Neither of these two grand narratives has proven capable of inspiring an actual mass effort to colonize space. Not because the physics or engineering are impossible; as O’Neill pointed out, we’ve been able to do it since the 1970s. The problem is that the individual has no agency in either vision, and the family does not exist as an independent economic and social unit. In the anarcho-neoliberal scenario, there are only corporations, oligarchs, and indentured workers in company towns. In the collectivist version, individual and domestic ambitions have to be subsumed under the overarching need to coordinate building and maintaining the giant islands—or funding Starfleet, etc. Company towns don’t accommodate slackers, incapacitated or elderly residents, or dissidents; on the other hand, O’Neill’s plan can only be achieved by a vast, coordinated, collective effort over many decades. There could be shining cities in the sky, someday; meanwhile, there will be no equivalent to the homestead that could satisfy our settlers’ innate biophilia while providing for a stable, independent, generational domestic life on a smaller scale.

Theme and Reframing: A home in the sky

So the deep problem that keeps us thinking about space settlement in mythological and fantastic terms—literally, as science fiction—is that the theme of family life, including multigenerational domesticity, is missing from our narratives. Understanding this, we can reframe the problem of space settlement this way:

The best way to kickstart the long-term settlement of space is if the average he, she, or they can own or have a legal stake there in the form of their own home.

What if you could move to space, but not into a tin can owned by somebody else? What if you could have a true space colony as O’Neill envisioned it, with your own house, a lawn and garden, maybe a swimming pool, trees and birds, and a blue sky—but on a scale that you, as a household, could afford? This is the missing piece in O’Neill’s grand vision.

This is the single-family space colony.