Design Your Imagination

They really ought to teach this stuff in high school

A week or so ago on Twitter/X, John Joseph Adams mentioned that he has aphantasia—he can’t visualize things in his ‘mind’s eye’. He asked how others rated themselves on the ability to picture, eg., a horse, on a scale of 1 to 6. Some said they were also ones or twos, and others, myself included, admitted to being off the charts. I said,

Definitely a 6+. I can see the horse in full color and rotate, add motion etc . with my eyes wide open. I trained myself to be able to this kind of thing in my late teens, as part of a deliberate program to hack my brain for ceativity.

But I added:

I started writing a post on my substack on the techniques I used (none drugs-related) but deleted it after looking at it and going "people will think I'm insane."

All this did was make Twitter more curious. The response was “come on! Tell us more!” That got me thinking about all the creative tricks and techniques I’ve learned over the years, many of which I take for granted. So, I’ll answer the call and describe how I trained my internal eye, emphasizing that it’s just one of the ways I hack creativity. I use lots of techniques. What follows is a list mostly from a writer’s perspective, so you may or may not find it useful if you do different creative work.

Let’s Start with the Hard Part

You can easily find articles and listicles about becoming more creative. Creativity, though, is only half of writing, and not the most important part. The important part is having something to say.

I’m pretty sure I’ve never read any articles claiming to teach relevance. But this is where you have to start if you want your writing (or anything, really) to last.

Luckily, society is experiencing rapid evolutionary pressure in this regard, because we all know AI is coming for any ‘creative’ work that can be defined and replicated. You can already generate entire novels with a few prompts, and the product is just going to get better and better. So what’s a human to do in the face of that?

Actually, it changes nothing. We were already drowning in an ocean of repetitive crap, and AI’s just going to widen the sea. It’s not going to change the fundamental issue, which is that our communication with one another should first of all be about something. Calling a text meaningful means you should be changed by reading it—and as an author, or a foresight worker who wants to shock your audience out of their assumptions about the ‘default future,’ your aim should be to open new vistas to people. Not just to re-present existing ones.

This is the hard part. Here are a few ways I try to feed my relevance:

Practice Horizon Scanning

Horizon scanning is the practice of constantly watching for what in foresight we call ‘weak signals of change.’ These can be anything—changes in peoples’ voting habits, a decline in shoe sales, the appearance of multiple airship freight companies in Canada despite none owning a functioning airship. Or a mad billionaire building a giant rocket in south Texas… oh wait, maybe that’s a strong signal of change. You should track those too.

But not to figure out what’s happening. The worst rabbit hole you can go down is trying to figure it all out. The point is to recognize that something is happening, by noticing when canaries start falling. Sometimes it’s enough to do the noticing, and bring the fact to other peoples’ attention. Smarter thinkers can figure it out; or, you can let your own imagination run riot over the possible reasons. Either way, you use horizon scanning to perceive and collect the new.

Be a Generalist

…Because if you’re a specialist, AI is definitely coming for your job.

The first principle of innovative thinking is to look for deep connections between seemingly incompatible domains. I say ‘look for’ rather than ‘impose’ because the hallmark of cult and conspiracy thinking is to start with a predetermined ‘truth’ and then try to find it in everything. All you’ve got is a hammer, so every difference in the world becomes a nail to be pounded flat. That’s the opposite of what you should be doing. You’re searching, without prejudice, and generally just letting ideas suffuse through your unconscious rather than trying to draw lines between them. When you one day find yourself using one domain (say, sports) to think about another (say, biochemistry), then you may have found something worth writing about.

So first, be interested in everything. You may never become an expert on a given subject, but that doesn’t mean you can’t contribute to understanding it.

Read Diffractively

Diffractive reading is an idea I got from Karen Barad. You do it by seeing one text or set of ideas through the lens of another, not judgmentally, but according to how each amplifies or mutes the other’s meanings. The way that interfering beams of light create diffraction patterns. For example, lately I’ve been thinking diffractively about space colonization (specifically Venus) through the diffractive lens of ecology. What if we consider humanity to be just one player in a much bigger ecosystem that has to exist before earthlings (people included) can permanently settle in space? I’m just applying the Copernican principle to space development: we’re not special. Considering all the complex technologies that have to exist to sustain us up there, the diffractive reading suggests that sustaining them is the precondition to sustaining us—and that therefore, up there they are more important than us or at least, should be autonomous from us so that human infighting is unable to take the whole system down.

Read to find commonalities and differences, not to figure out which of two perspectives is ‘truer.’ The bright bands where ideas reinforce one another can become genuinely new ideas.

Be Wrong

Don’t stick to the facts. Instead, try to be wrong sometimes. Just be aware when you’re doing it. Going down a blind alley convinced that it’s the right one is a very bad idea; but one of the things I like to do when I visit a new city (at least in Europe, where I feel safest) is to go walking and get a little lost. Loosely holding a set of contradictory beliefs in mind is useful, especially when you’re writing fiction.

Fiction is the art of perspective.

Read the Edge Thinkers, Avoid the Nutcases

You can afford to be a little wrong when you start by learning the consensus view on a topic, then search for authors whose ideas disagree with that consensus, but are cited by everybody. These are the interesting ones to read.

This is a great tool for filtering out the crazies while finding the visionaries. For instance, take Ayn Rand. If you read broadly (even if shallowly) through mainstream 20th/21st-century philosophy, you will discover that nobody outside her circle talks about her. Nobody cites her. On the other hand, people may only talk about Alfred North Whitehead to disagree with him, but he’s cited across the literature. This suggests that Whitehead is an edge thinker, while Rand is uninteresting. (There are other reasons to think that Rand is a nutcase, but we needn’t go into them here.)

When you find edge thinkers, study them. They’re pure gold.

Start with the Deepest Puzzles

I’m a science fiction writer; that is to say, I use scientific possibility as one of the constraints I place on what I can write about. This is just one of the personal rules I follow, but it’s gotten me labeled as a “hard SF writer” for some reason. Hard SF is generally considered engineering porn, it’s about devices and systems and what-if scenarios more than people. But I never saw my own work that way. Keeping the science straight has the same importance as, say, continuity or consistency of tone.

—Anyway, the point is you can float on the surface of anything—sports, murder mysteries, science fiction—and the work you will do will be… fine. Just fine. Or, you can dive deeper into the existential and philosophical and political agonies that lie under these clean surfaces. That’s where truly new ideas lie in wait.

Always Reinvent the Process

I never knew how my late editor, David Hartwell, would respond to my work. For one of my books he said, “I like it but you need to chop 30,000 words. And make the hero five years older.” For another, he invited me down to his house in upstate New York to do a line-by-line pass through the entire book. It took days. For yet another he said, “I like it but take out this one sentence on the second-to-last page.” He reinvented the editorial process on a book-by-book basis.

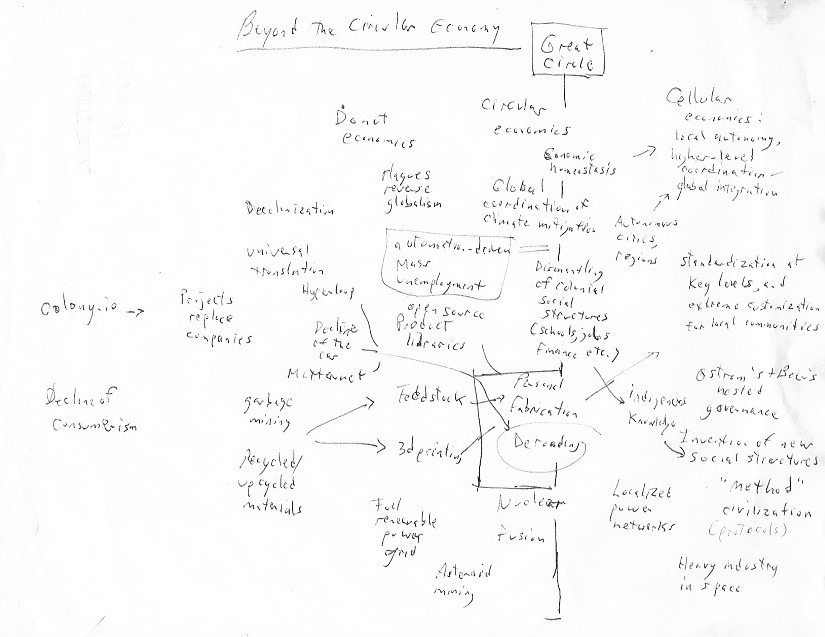

I do this with writing, at least on the novel level. For one story I had a 20,000-word detailed outline. Another, I did the entire thing from one hand-written page of notes. I’ve been known to dog-ear books, bookmark like crazy in the e-reader, or cut and paste ideas into OneNote. And then never look at them. Sometimes I keep all my ideas in my head. Sometimes I do mind maps like the following:

Mostly I don’t. Each creative project is its own thing and has to be approached as if you’ve never done this before. You’re always a beginner in some sense, unless your aim is to find a formula that works and just crank ‘em out. That could make you successful, but it also means I’ll only need to read one of your books.

Getting Back to That Aphantasia Thing…

I’ll be posting soon about my daily writing routine, including how I break writer’s block. To anticipate that a bit, I’ll say that reliably summoning your imagination is a skill tied to letting go. How creative you can be is hugely dependent on how good you are at disengaging the critical-thinking part of your brain while you’re simultaneously engaged in a task that demands discipline. Take painting or the development of a new storyline: these are tightly constrained working environments and you work in them using a pretty regimented skillset you’ve likely built up over years of practice. This means you run in ruts much of the time. Breaking out of those ruts requires handing over control to unconscious parts of your mind, on command and in a controlled way. This is very hard to do.

Many of us have our best ideas while drifting awake in the morning. Yesterday I came up with the scenario for a potentially vast science fiction epic while in the shower. People have known about this trick for centuries; there’s a long history of artists using different techniques to enter the hypnogogic state. For creative inspiration, Salvador Dali used to sit upright with a pencil tucked under his chin in such a way that, as he drowsed, it would dislodge and wake him if he actually fell asleep. He wanted to be as close to sleep as possible without going all the way. Balancing, like a pencil on its end, between waking and the hypnogogic state, he could maximize his creativity.

Creativity is the paradoxical art of guided letting-go. I was lucky to learn this very early on, when I was just 17 and working on my first novel. It seemed to me that if this was the case, it must be possible to train yourself. I read about Dali’s technique and it didn’t appeal to me. But there were other possibilities.

Repurposing Meditation

I was already reading for the edge cases, and sometimes the edge cases really are also nutcases—so I was cheerfully plowing my way through Aleister Crowley’s book Magick at the time and thoroughly enjoying his pseudo-intellectual shenanigans when I came across his long, detailed description of meditative discipline. He describes it, basically, as the fight of your life. The specific technique he espouses (which is the opposite of mindfulness and likely the only one he knew about) involves fixing your attention on one thing and keeping it there for minutes, hours at a time. In retrospect Magick was the first time I read a description of what it is like to have ADHD—both how hard it is to keep your attention from wandering, and what the almost savage point-light of hyperfocus feels like.

Crowley’s whole schtick was that you had to keep up this fight to achieve Nirvana, and he wastes a lot of ink describing that epic battle. He didn’t convince me that Nirvana was necessarily where I wanted to go right then, but the way he described the fight made me sit up and take notice of something.

He says that at a certain point the meditator will notice how the mind is always throwing up distractions, in the form of half-finished thoughts, a ceaseless inner monologue like Joyce explores in Ulysses—but he also speaks of half-glimpsed images and voices, music or sounds that are normally below the threshold of conscious attention, but are always there.

Always there? Now that was interesting. He was saying that the hypnogogic state is not a place we can only go to at night; just as the stars are only invisible in the day because daylight outshines them, it might be that a vast river of hallucinatory images and sensations is passing through us at every instant, even when we’re wide awake. It’s just too dim to be seen; the light of consciousness washes it out.

I decided to see if I could tune into it to the point where I could summon dream-imagery anywhere, any time—deliberately do something similar to hallucinating, but in a completely controlled way and without losing the ability to tell fantasy from reality.

And I did. I fought the mental fight of meditation Crowley described, but when I began to notice images and sounds—as he said I would—I didn’t try to suppress them, as he said you should. I doubled down on noticing them. I learned to become mindful of them, and gradually, how to flick my attention away from my real surroundings and look into a different world at any time. It’s like riding a bike; once you learn it, you always have it. I’ve been able to do this for almost half a century, and it’s a skill that has come with no psychological ill effects (unless becoming a science fiction writer is one of those).

It’s not always useful, I hasten to add; as I’m writing this sentence I’m just checking and… looking through the laptop screen and my living room I see a lake with choppy waves, a forested shoreline on the right and other higher peaks past the far shore, which is about three kilometers away. Anytime, anywhere, I can trip a mental switch and see something like this. It’s different every time; and that lake’s not particularly interesting. The disappointing side to this skill is that its products are seldom relevant to the present task.

What’s the difference between doing this and just imagining something, you ask? It’s about intention. If I say, “imagine a horse,” most people can do it. But if I say, “imagine!” not many people can immediately say that they see something and name what it is. If you command me to “imagine!” I will instantly be presented with an entirely different place, adjacent to the real world and with wholly unpredictable content.

What I’ve described here is visual, because I’m a very visual thinker; but you can do the same with spoken words or sound. Simply put, there is more than one internal monologue in your head at a time, but one has its volume ratcheted up while the others are turned way down. It doesn’t mean they’re not there, though. I bet Mozart, engaged in conversation with someone, also listened to random melodies playing in the back of his head—not crafting them, just being mindful as they arise and fade away on their own. This is a skill you can learn.

But Don’t Get Distracted

I learned daylight hypnogogia, added it to the toolbox, and I pull it out when I need it. By now, the toolkit is vast; it got even bigger when I entered the Master’s program in Strategic Foresight and Innovation at OCAD University. Who knew there was a whole separate skillset, running parallel to science fiction, but with entirely different methods and aims?

Foresight, how it differs from science fiction, and why it’s powerful and relevant, deserves a deeper dive. I will talk about it in more detail, but not today.

For now, I’ll say that creativity is cool and all (as is daylight hypnogogia), but it’s just part of the toolkit, and creativity isn’t even the point. Relevant creativity is the point. That comes from constant scanning, testing, and reinvention.

Circling back to the reason I started this newsletter in the first place:

If you want to cultivate an unapocalyptic mindset, continuously reinvent the future. How you do it is beside the point; but do it.

As a creative (puzzle designer) with a now-distant background in engineering, I recognize all of these techniques. So at the very least, you can count this as +1 on your validation scale.

Thank you for writing this up, Karl. I enjoyed the diversity of influences. from Crowley to futurists.