Apocalypse as Design Constraint

Strangely, by limiting possibilities, we end up having more than we started with.

The Secret World of Constraints

In “Who Paints the Dew on the Daisy” I talked about how we all use one or more ‘theories of change’ to understand the world. I said that my favourite theory of why and how things change is constraint. I promised I would write more about it because it’s a perfect example of what I’ve been calling 21st-century thinking and is crucial to my design practice.

Constraint is a well-defined concept that’s been used in physics forever, but like complementarity, it’s only fully flowered in this century. Its lessons haven’t broken through into wide public discussion. Notable exceptions are pushing for such a conversation, including Stuart Kauffman and one of this generation’s most influential dynamical systems thinkers, Alicia Juarrero. She has a new book out that I highly recommend: Context Changes Everything.

There’s been a long-standing assumption among cognitive scientists that conscious states are “epiphenomena,” that is, they are the products of (or the same as) neural processes in the brain but have no causal power themselves. That would violate the thermodynamic closure of the system. Basically, your consciousness is just neurological exhaust; you don’t really exist, the thing you think of as yourself is just a helpless observer watching from outside the world as your body steers itself through life.

This is a dumb idea for a lot of reasons, but Juarrero shows exactly why it’s false in physical terms, and further shows how non-physical entities such as ideas, attitudes and political movements can have their own causal force that is greater than the sum of their constituent causes. The top of the pyramid (mind) really can reach down to change things at the bottom (matter and energy), without violating any physical laws. Constraint is the seemingly magical influence that makes this possible.

Constraint is Good

Let’s say I give you a jar of marbles and tell you to pull out three at random. You do this several times. Each time, you find that either all the marbles are the same color, or that two of them are and the third is a different color. What is causing this strange behavior?

It’s a trick question: there are only two colors of marble in the jar. This is all there is to it. The fact that there are two colors is the constraint that results in any set of three marbles either all having the same color, or having two the same. Nothing causes this behavior; it’s a result of the situation—the context, as Juarrero puts it. And context, as it turns out, is everything.

The marbles example is from Marc Lange’s book Because Without Cause. So is this one, which is a little less intuitive: there are always two points opposite one another on Earth’s equator that are exactly the same temperature. If you can figure out why you win a… I dunno what you win. But you’re smarter than me, because I don’t get how this works. The point though is that nothing causes that phenomenon; it’s just the nature of the situation for it to be so. One of Juarrero’s examples is traffic circles, which do not use any force to compel cars to take the correct route around them. The route is made inevitable by the roundabout’s geometry plus the presence of drivers with destinations.

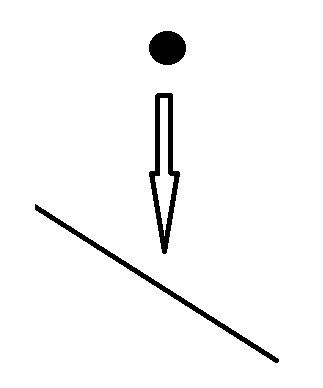

Constraints bias probabilities. They make some outcomes less likely, and others more. In the following image, the inclined plane creates a constraint on which direction the falling ball is likely to bounce. It does not exert an extra force to do so.

We think of constraints as limitations. We focus on the possibilities they bias against because these can be known in advance. What constraints bias a system towards is not always easy to see—and everything hinges on this fact.

Our lives are wracked with constraints. We only have so much money, time, and health; we live in a particular place that maybe has few opportunities for us but we can’t afford to move; we are limited by education, gender, class, and race. More widely, there’s war in Europe, insane global temperatures, and a hopeless divide between rich and poor. Oh, and a pandemic that nobody seems to want to talk about anymore. These are all constraints on our ability to live complete, fulfilling lives.

In nature, the constraints imposed by thermal and chemical gradients, mineral distribution through the Earth’s crust, oceanic and solar energy—these create more and more interlocking restrictions on how energy can flow, until thermodynamics gets thoroughly boxed in; its only way out is to start favoring complexity over simplicity. The result: life, humanity, and mind and all of our accomplishments. None of those are predictable from the entailing laws of physics. No force of nature can account for the dew, or the daisy. To put it another way, a second after the Big Bang, nothing in the laws of particle physics hinted at the possibility of rivers, misty dawns, or human beings. These only became possible as more and more constraints piled onto the initial soup of particles.

The creativity of the universe doesn’t emerge until constraints come into play. This means that things never before seen can appear when the right constraints are in place. It also means that before they appear, there can be no hint of what’s coming.

Stuart Kauffman calls this creative side of reality the adjacent possible. By its very nature, its products cannot be known in advance.

Which brings us to our present moment. We live in an era of increasingly powerful constraints. Everything we do makes our ecological situation worse; our post-capitalist economy has with the help of technology become a giant machine for concentrating wealth. (AI will only make that worse, by the way.) Our societal immune responses to fascism, propaganda, and inequality no longer seem to work. The young aren’t respecting their elders, or whatever. The point is, our existing repertoire of responses doesn’t seem to work anymore. Because we can see constraints coming ahead of time but not the new behaviors they make possible, it feels to us as if we’re running out of options, personally, and collectively.

But that is not what’s happening.

To give just one real-world example, anyone who was paying attention in the late 90’s knew we were entering an era of progressively tight restrictions on fossil fuel use. Nonetheless, no reputable futurist I’m aware of predicted that by the early 2020s, battery costs would fall by 97%, solar power prices by a similar amount, and that in 2024 more than 3 gigawatts of power would be flowing into Britain from North Sea wind farms alone. The impending constraints were visible, but not the new innovations that would result from them.

We all know we’re plunging into a future of radical, rapid change. We have to decarbonize completely and immediately, for instance. Fine, we see the limitations.

What epochal opportunities do these constraints make possible for us?

In the remainder of this article I’ll talk about how we can celebrate constraints, even using them as a generative model to figure out new solutions for our problems. I’ll show how you can do this using an example from writing: how I designed the world of my novel Lockstep. I’ll end on a note of (I hope) earned optimism about our future.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unapocalyptic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.