After the Internet

There is no "online world." That was always a metaphor, and as it turns out, a bad one. But what can take its place?

In our usual spirit of questioning the unquestionable, let’s consider whether the Internet is really a thing.

There’s a history to the idea of an ‘online world.’ It’s explicitly a science-fiction construction, and you can see exactly who popularized it and when. Two key names in this history are William Gibson and Neal Stephenson, who coined “Cyberspace” and “the Metaverse” respectively, as descriptions of a mythical digital space where dramas could be placed. That’s what the Internet-as-a-place is: a literary setting. This is a metaphorical construct, and more than that, a storyteller’s convenience, similar to the transporter in Star Trek that made interminable cut-scenes showing shuttles flying to and from planets unnecessary. Cyberspace as a concept doesn’t demand anything of us, because we were raised on stories about parallel worlds, the astral plane, heaven, and hell. All Gibson and Stephenson needed to do was file the serial numbers off of one of these and give it a fancy technological name, and just like that they had a new playground of the mind that people could relate to.

I’ve noticed over the years that engineers tend not to notice the artificiality of these mythopoetic metaphors. An entire generation of computer geeks devoted their lives to making the cyberpunks’ analogies real, quite uncritically. Critiques and alternatives were offered during the making of the Internet-as-place (Brenda Laurel’s Computers As Theatre comes to mind), but Internet-as-place was such a powerful conceptual metaphor that it steamrollered any alternative vision. This had consequences, as we’ll see.

I’m going to suggest that the Internet-as-place metaphor has had its day and that what could replace it is a radically embodied, localized alternative. This would be a technological, social, and conceptual shift; there are multiple drivers at work here.

If we stop treading on the Internet as a stage, whole new vistas open out. For science fiction writers, there are entire careers worth of potential here.

Could It Have Been Any Other Way?

Was the Internet as we understand and use it today inevitable? If we had an alternative to compare it to, we could argue that it wasn’t. And an alternative did exist—briefly.

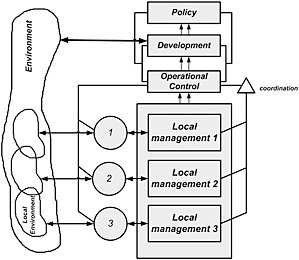

From 1971 to 1973, Chile organized its government-owned enterprises via a system called Cybersyn. We laugh at it now, as computers were huge and expensive back then and Chile only had a warehouse full of teletype machines to implement Stafford Beer’s vision of a cybernetic state. Yet as Beer pointed out in his books and lectures, after a certain point, more information does not make decision-making any better. Cybersyn wasn’t a poor man’s Internet; it was not designed to heave vast amounts of data around, only exactly what was needed to generate awareness of a situation and shape a response to it. Cybersyn was a cybernetic network in all the ways that the Internet is not: sparse, efficient, fast, and aware of the nonlinear responses that networks of agents can surprise us with.

If you use the Internet-as-place metaphor to judge Cybersyn, you will find it primitive and woefully crippled; and you’ll completely miss the point. The conceptual metaphor of Cybersyn wasn’t network-as-place but nested viable systems. A viable system can function as a semi-autonomous entity. It has defined inputs and outputs and uses a structured feedback system to maintain homeostasis. Most importantly, you can build viable systems out of other viable systems. This was what 1972 Chile was: self-governing public goods like nested Russian dolls, where each entity making it up had the freedom to solve problems on its own—no centralized control here, which is why it worked and why it was democratic. Only if a subsystem stopped fulfilling its function would a manager from a higher level system drop by to find out what was going on and maybe intervene.

So yes, an alternative paradigm for national, regional, and even global networking does exist, and was tried. What Cybersyn was is unrecognizable if your only model of networked computing is the World Wide Web. (If all you’ve got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.) Cybersyn promised a “third-way” alternative to capitalism and communism, where the network wasn’t a vast pipeline for flooding the world with books and accounting data and emails and pornography; it was just the lightest nervous system needed to support a just and free society.

It didn’t fail on its own. It was violently suppressed.

We Got The Other Guy

Dazzled by the cyberpunks, the engineering geniuses of the United States and Europe repurposed a cold-war messaging-redundancy system called Darpanet, and gave us the Internet. A place. An online world. In the 1990s, that was pretty exciting, and only a few of us could be heard mumbling that maybe yearning to upload in a glorious Rapture of the Nerds was, um, maybe, a little unhealthy?

Websites were the most successful attempt to turn the abstraction of distributed message passing via the TCP/IP protocol into a set of places you could visit at your leisure. Back in the day, the expectation was that there would be a natural evolution from these to virtual spaces we would visit in VR. Second Life tried to build the Metaverse with exactly this expectation. Somehow, VR never caught on, and Second Life, while it’s still around, has not evolved into the successor to the Web.

Around the same time, a competitor to the Internet-as-place metaphor developed, around the RSS and RDF standards. RDF was an attempt to turn the Web into a single coherent database—not mediated by Google—based on semantic tagging. The idea here was that, rather than duplicating the localized notion of a storefront online, the Internet should simply be all the world’s knowledge at your fingertips. Cory Doctorow and I worked together to create such a website-free knowledge aggregator at OpenCola, a Dot-com-era startup that ultimately went the way of most such startups. Cory and I strongly believed that the Internet is a commons, and while one might build business models adjacent to it (as Red Hat did adjacent to the free Linux OS they distributed), the commons itself must not be enclosed.

When the dust of the great Dot-com bust settled, Google, Facebook, and Amazon dominated, and they planned to enclose that commons. They succeeded pretty well—to see just how well, look at the one exception that proved the rule: email. Email has continued to be free and uncontrolled by any monopoly, although recently Google has stealthily begun de-registering vulnerable domain names (like mine). The trend is clear: the commons is being enclosed, and soon what was free will cost you, for no other reason than that powerful interests have found a new way to pull money out of your pocket.

This, anyway, was how things were going, until Generative AI came along and spoiled the party.

The characteristics of the modern Internet were not inevitable. Far from it—they are the result of a historical process, and alternatives were possible and were tried.

The Antinet

In 2018 I published a short story, “Noon in the Antilibrary,” in the MIT Technology Review. (You can read it online for free.) It explores the question of just how detailed and pervasive deepfakes can get. The story’s depressing answer is, “as detailed and pervasive as you can imagine.” The antilibrary is a generative AI system that can produce entire librarys’-worth of fake books with fake authors, fake citations by other fake experts with their own fake books and biographies and fake social media accounts, on-demand and instantly. It was speculation in 2018; it’s possible now. Creating an antilibrary is just a matter of investing in a sufficient number of graphics cards and electricity.

Beyond the antilibrary is the Antinet, a completely deepfaked version of the Internet entirely customized for each user. The Antinet is a kind of “bubble reality” for individuals that makes them trivially easy to manipulate. It contains just enough common material that when people compare notes, there seems to be consistent data out there. But there isn’t. The Antinet is entirely made up, utterly mercurial, and exists to control you in all the ways that Cybersyn didn’t. It is the 21st-century version of Orwell’s Ministry of Truth. We are about one technological step away from building the Antinet. [Correction: Websim.ai means we are already there.]

The Antinet increasingly seems inevitable, because instead of the semantic web that Cory and I were pushing, we got Google and Amazon, and an atomization of information. If every news report and article on the Web had been interconnected to begin with, with a chain of attestation you could follow back to empirically verifiable truths, we wouldn’t be in this situation. As it is, every file and fact is its own thing, unconnected to anything else, with the result that every ‘truth’ on the Net has equal authority.

The corrosive decay of trust in authority that has been accelerating since 2001 is about to kick into high gear. Social media put us on the starting line, but social media plus universal deepfakes will make all online information unverifiable. Since even our TV comes to us over the Internet now, it won’t be trustworthy either.

I can see two possible responses to this situation: people either believe what they’re told because they frankly have no other option; or, they abandon the Internet as a source of facts. It becomes purely an entertainment medium. The only ground for truth in this world is direct, personal experience, and the face-to-face statements of people you trust.

Let’s Go Outside

Did we even want the Internet that we have in this century? I don’t think so, for a variety of reasons. One major one is the general principle:

If you have to use (interact with) a computer, then it’s not doing its job.

Computing is useful insofar as it removes the need for a person to perform a particular task. Drive engagement is exactly the opposite of what you want a computer to do. By this logic, our computers should be becoming increasingly invisible. They should be reducing our cognitive load, not increasing it.

I take this to be the reason why VR has never caught on. VR (and by extension, any ‘online world’) demands that we attend only to it. It’s the ultimate attention-hog, but returns no unique value in return for our engagement. If your business model is based on user engagement, like Facebook’s, then the Metaverse, being the ultimate engine of engagement, will be what you rebrand and bet your company on. But it’s a losing bet, because as Gertrude Stein said about Oakland, “there’s no there there.” There is no reason why an embodied consciousness like ours should spend its time in any world but the one where our bodies live.

There’s even more to the metaphor that there’s no “there there.” Internet-as-place is a conceptual metaphor that dovetails perfectly with Globalism; for a great analogy, compare it to the International style in architecture. The end result of the International style’s success is that every major city in the world looks the same now. That’s the idea, of course—to annihilate differences of location so that there is only one place, one City. Every place is interchangeable with every other one. This papering over of differences feeds the philosophy of the “view from nowhere” that is also embedded deeply in technological science: it’s the idea that once we have all the principles and laws of nature in hand, we can ignore individual differences. Some profoundly unhealthy loathing for the reality of the natural world is being expressed here, and it merely papers over the particular, temporarily. Nobody wants it. I doubt that many of the office towers dominating the world’s skylines will still be there in a hundred years.

The “view from nowhere” has been a key enabler of the environmental devastation we’ve wrought over the past century. From this perspective, one lake or river is the same as any other, so polluting this particular one makes no difference. A lake is a lake. Generalize this attitude to the actions of thousands of companies and governmental agencies around the world, and you get permanent no-go regions, oceanic dead zones, and ultimately mass extinction.

In ironic contrast, by projecting the image of persistent “locations” on an imaginary surface (the Internet), the Web and related technologies send a message of stability and solidity that the underlying tech doesn’t justify. Everything about the Net is ephemeral; it’s a monumental exercise in keeping plates spinning, and the increasing monopolization of its infrastructure makes single-point-of-failure crashes—such as the July 19, 2024 outage—more likely.

While all of this was going on, of course, we had the parallel development of location-based computing in our cell phone networks. Here the architecture is slightly different because what we want to do with our phones is different. Knowing the impending weather right where you’re standing is more important, so our phones are the battleground between the “view from nowhere” and location-based services. Amazon really wants you to visit their site through your phone, but phones are conversational devices, and it’s likely here that AI interfaces such as ChatGPT and Claude will first crack the Internet-as-place metaphor. When you can just ask your phone to find, summarize, or buy something for you, and you’re no longer interacting directly with Google and Amazon, they cease to be essential intermediaries in your dealings with merchants and individuals. At best, they become infrastructure used by your AI. At worst, they’re monopolistic barriers that it will seek to route around.

Embodied, Localized Computing and Your New Best Friend

When phones have NPUs built-in and efficient localized Large Language Models and agent swarms, we could end up with a new conceptual metaphor for the Internet: Internet-as-person.

The AI consolidates all the data you’re looking for, and manages interactions with eg., stores and services, in the background. I hope there’ll be robust open-source versions of these AI agents, so we don’t continue to be locked into the walled gardens of monopolies owned by the billionaire bros. Critically, their AIs have used up the available online data to train themselves; to get any better, they’ll have to leave it and start gathering information themselves. Tesla’s cars already do this by acquiring real-world data as people drive around, and they use that data to help train the FSD (Full Self-Driving) AI. Their robots will do the same; although they’ve gotten off to a shaky start, humane.com are showing how your personal AI may learn your preferences and habits in much the same way. There are gigantic privacy issues with this tech, obviously, but the potential is huge. Consider that a lapel pin sensor connected to an AI on your phone could passively watch where you go throughout the day, and when you need shoes repaired, for example, you can just tell it and it will say, “actually, there’s a shoe-repair place on your regular route to work…”

While the global network is still there in the background, your interactions with it are increasingly contextualized and based on your embodied experience rather than the “view from nowhere.” You’re interacting with a kind of Infosphere, but arguably no longer the Internet as we’ve come to understand it. Your agents, meanwhile, are likely to use tunneling, cryptography, and trusted partners to fight deepfakes. They’re likely to become even more skeptical of online sources than we are, and more determined to find real-world eyes that they can use to verify assertions. The future of trustworthy AI is embodied, evidence-based, open-source, and localized. Maybe Laurel’s computers-as-theatre metaphor will win out in the end.

Such a system might help us minimize our direct interactions with the Infosphere, fulfilling the ultimate purpose of all computers: to get out of our way.

A New Cybersyn?

There was nothing inevitable about the way the Internet developed. There is nothing inevitable about where it will go next or what might replace it. But as a metaphor, Internet-as-place seems exhausted, and the Metaverse less and less palatable as a destination.

When we look back on today, it may be obvious that our constant, direct engagement with a metaphoric space was a brief pathological phase, and that Internet-as-place was always a doomed metaphor. Looking forward, other metaphors and uses of networking technology are possible; most importantly, when we abandon the idea that the purpose of these networks is to enable us to drink from the data firehose, then perhaps we can return to the cybernetic model of networking exemplified in Cybersyn. In this model, we’re not trying to consume data to think with, but rather signals to help us regulate and manage our lives. A new Cybersyn could provide the “third way” of post-capitalism that so many of us are looking for, enabling efficient coordination and feedback-based democratic control over our economies.

Such a potential future presents science fiction with an historic opportunity. It’s time to relegate cyberspace to the quaint past of blocky robots and space opera, and imagine new networks. Ruthanna Emrys does this in A Half-Build Garden, as do L.X. Beckett in Gamechanger, and Malka Older in Infomocracy.

I’ve yet to read the definitive next-gen Cybersyn thriller, so maybe I’ll have to write it myself.

One thing is clear: things could be different. Science fiction can take the lead in showing us alternatives to the Internet, which could be both fun, and liberating.

Let’s get to work, and make these visions real.

—K

Terrific meditation, Karl. Internet as person sounds compelling for people who prefer to anthropomorphize.

"The “view from nowhere” has been a key enabler of the environmental devastation we’ve wrought over the past century." Naomi Klein makes a similar argument in her climate change book, arguing that the view of Earth from space is deracinating (in a bad way).

your "one lake is like another" metaphor coupled with your AI on a clip following you around seems to be the problem. If the AI can "learn" your "personal preferences" then when does it get to the point where it just eliminates the flesh like your on-button on your computer knowing your finger prints.

I just replaced my basic iphone and already it has linked and interacts with the apps on my system without my involvement except it does ask permission (sometimes). When will it be able to choose where I buy my coffee and breakfast? what about the idiosynchrasy in life?

one can wonder whether the ultimate is this uploading of our brain into a digital person and discarding the inconvenience of a "flawed" flesh

------------